The ancient harbor of Marseille (Lacydon).

-

In the 7th century BC, the Greek navigators and colonists appeared in almost all the Mediterranean coasts, managing to settle in the greater part of them. In the coast of Western Liguria (modern SE France) the Greeks encountered the Celts for the first time after the Mycenaean era. But when they arrived in the region as traders (8th century BC), the indigenous inhabitants were the Ligurians (Ligures), a people of Neolithic origins who had adopted centuries ago a variety of the proto-Celtic Urnfield culture. The first Greek settlers – Rhodians and Phocaeans from Asia Minor – founded a trading post at the modern site of Saint Blaise which soon became a real city, possibly with the name “Heraclea” or “Mastrabala.” But soon afterwards, Heraclea-Mastrabala declined due to the deposition of silt in the estuary of the Rhone River that disabled the city’s harbor. Heraclea was overshadowed by Massalia, a new Greek colony founded around 600 BC in a better site.

The foundation of Massalia (modern Marseille) was a major event in the history of the Gauls and generally the Celts, strongly affecting their ethnogenesis, culture and evolution. The Massaliot cultural influence in the Celtic Halstatt and La Tene cultures (through trade and other relations) was especially important. The commercial network of Massalia used the major rivers of Gaul (Rhone, Loire, Garone, Seine et. al.) reaching the North Sea and the British Isles. The Laconian crater excavated in modern Vix of Northern France is a famous artwork which was brought there by Massaliot merchants on behalf of the local royal family. Numerous Greek elements were adopted in the Gallic culture, ranging from everyday life to artistic expression. Marseille ‘exported’ to the Gauls its own Ionic culture (the Massaliots were Ionic Greeks) and simultaneously functioned as an “intermediary”, spreading in the same people the technology and the culture of mainland Greece and the Greek colonies in Italy (Magna Grecia). The city grew rapidly becoming the commercial harbor of most of the Gallic world, whose products were channeled to Massalia and then they were distributed to markets in the entire Mediterranean. The Mediterranean products followed accordingly the reverse path, reaching finally the Galatian customers. Massalia was the commercial and cultural “gate” of the Celts to the South. One of its most important contributions to the Celtic world was the Greek alphabet, which was spread to Gaul and a great part of Britain.

The Laconian crater excavated at Vix.

-

The Phocaeans of Asia Minor were the founders of Massalia. The Gallo-Roman historian Pompey Trogus quotes (through the book of Justin) the city’s foundation legend. According to him, Phocaean seafarers led by Protes, left their homeland in order to establish a colony. After a long and dangerous journey, they arrived at the estuary of the Tiber, the port of Rome (Ostia was not founded yet). The Romans were friendly to the Phocaeans, and now they allied themselves with Protes’ men and gave them supplies for their ongoing colonist mission. From Rome, the Phocaeans sailed to the coast of modern Provence. The Greeks landed in the territory of the native Segobriges and their king, Nannus, welcomed them. They landed there in the same day that Gyptis, Nannos’ daughter, would choose a husband. According to the local customs, the princess would make the selection during a symposium in which all the scions of the local aristocracy were invited. Nannus invited the Greeks as well in the symposium, without considering the consequences of the invitation. The king gave a cup of water to his daughter, asking her to offer it to the man who wanted as a husband. Gyptis passed indifferently the Ligurian suitors and offered the cup to Protes. Nannos was obliged to give his daughter’s hand to Protes and also a part of his realm for the foundation of the new city Massalia.

Behind Trogus’ romantic and possibly naive narrative, lies the historical reality. In my opinion, it seems that there has been some agreement between the Greeks and the Ligurians with the obligation of the natives to concede lands to the newcomers. This agreement was sealed by the marriage of the Greek leader and founder (‘oekistes’ in Greek) with the Segobrigian princess. Both sides benefited from this agreement. The Greeks were allowed to found their colony, while the Segobriges had on their side a military powerful ally for their wars against neighboring tribes. I must note that the Segobriges were supposed to be Ligurians, but their tribal name is Celtic. Probably their royal dynasty and possibly a part of their aristocracy were already Gallic, thence their Celtic national name. But there is also a theory on the language spoken by the Ligurians in those centuries. According to this, the Ligurians abandoned their own language when they adopted the Urnfield culture, adopting with it a form of proto-Celtic. This is also an explanation for their Celtic tribal name.

The original small Greek settlement of Massalia became gigantic with the passage of time, removing more and more land from the natives, now threatening their own existence. It was a situation very similar to the colonization of the English and French in the East coast of North America, at the expense of the Indians. Comanus, Nannus’ successor, was planning to reverse this threatening situation. The Massaliots already mistrusted the Ligurians and allowed them to enter the city only after their disarmament at the gates. Comanus had plans to conquer the city with treason during the great Greek feast of the Anthesteria. According to his plan – not surprisingly, a variant of the Homeric episode of the Trojan Horse – a group of armed Ligurians would be hidden beneath the foliage of the chariots of the festive parade and thus they would enter the city, waiting in their hiding places until dark. In the night they would open the gates of Massalia for the assault of the Segobrigan army, which waited hidden behind the neighboring hills.

The Greeks were lucky because a native woman revealed the Ligurian plan to her Massaliot lover and he immediately informed the city’s leaders. In the day of the Anthesteria, the Greeks were prepared. They attacked first the Ligurians and massacred Comanus with 7,000 of his men, almost all the warriors of the tribe. The Segobriges were almost extinct. It is possible that the episode of the Ligurian plan for the conquest of Massalia is a myth. Most probably, the ongoing expansion of the Greek territory at the expense of the Ligurians, resulted in a total war between the two peoples. Apparently the Greek colonists (although far fewer in numbers) managed to defeat overwhelmingly the Segobrigan army, due to their superior military equipment and tactics.

Greek (in red) and Phoenician (in yellow) colonies in the western Mediterranean.

-

After Comanus’ attempt, the attitude of the Massaliots changed dramatically. Their society became closed, robust and significantly militarized. The other Greek merchants and seafarers who arrived in Lakydon, the harbor of Massalia, observed that her citizens were always unsmiling, serious and strict. The small Massaliot army became very effective, due to the continuous and hard training, while their navy became one of the strongest in the Mediterranean. The development of Massalia was rapid. Her people subjugated the neighboring Ligurians and annexed the aforementioned neighboring Greek city-state Heraclea-Mastrabala (around 520 BC). They also founded many colonies, ‘channeling’ to these the new Phocaean and other Greek colonists who arrived in Lakydon. Famous modern French and Spanish cities were founded by the Massaliots or the Phocaeans. In France, Nice (ancient Greek Nicaea), Antibes (ancient Greek Antipolis), Arles (Thelene), Avignon (Avenion), Agde (Tyche Agathe), Monaco (Monoecos Heracles Limen), Saint-Tropez (Athinopolis), Cannes (Cannes), and in Spain, Alicante (Acra Leuce), probably Barcelona (Callipolis) and possibly Valencia and Elche, are only some of them. Other major Greek colonies of the same coasts were the cities of Tauroeis, Olbia, Emporion, Rhode (a Rhodian colony), Zacantha (a Zacynthian colony), Alonis, Pergantion and Hemeroscopeion. The Massaliot sea-fighters repulsed many seaborne attacks of the Etruscans, the Carthaginians and the Ligurian pirates, winning many victories.

The Massaliot naval force was so strong that it limited the powerful Carthaginian/Punic navy in the sea area south of the Balearic Islands and put under the Massaliot control the entire coast from modern Alicante (Spain) to Genoa (Italy) (Genoa was an Etruscan colony). The Late Classical Massaliot state comprised most of the 80,000-100,000 Greeks of the Far Western Mediterranean and had under its direct control an area of about 3-4,000 sq. Kilometers (the Classical Athenian state covered an equal area together with the Aegean islands of Imbros, Lemnos and Skyros), while the Massaliot political influence extended to another 8-9,000 square Kilometers of territories of the indigenous peoples (Ligurians and Iberians). It seems that the only other Greek cities of the ‘Far West’ (from the ancient Greek point of view) which were independent from Massalia but only occasionally, were the cities of Emporion (Emporium), Thelene, Rhode, Zakantha and Nicaea.

The city of classical Massalia (5th-4th centuries BC) had a population of 40,000-50,000, equal to that of the major ‘double cities’ of mainland Greece, Athens-Piraeus and Corinth-Lechaeon. The Massaliot army consisted of Greek hoplites and Gallic and Ligurian light armed subjects and mercenaries. The Massaliot cavalry was also renowned: the Romans awarded it credits for its action during the Second Punic War in the Rhone valley. Even more powerful was the navy of Massalia, comprised initially of penteconters and biremes and later (Classical period) of triremes, and during the Hellenistic period possibly quinqueremes. Massalia had a significant arms industry because of her militarization, several of which she exported to the Gauls of the hinterland.

The unfortunate thing for Massalia was that her history was mostly written by Latin writers. The city was rather distant for the metropolitan Greeks. Thus the ‘super-patriotic’ Roman writers (among them the Greek Polybius as well) ignored significantly her history or reduced in many cases her contribution in the subsequent Roman successes, e.g. the important role of the Massaliot navy in the victory of the Roman fleet against the Carthaginian navy in the estuary of the Iber River (217 BC) according to modern French historians. An English historian aptly notes: “The History of ancient Massalia appears to the modern world as the tip of an iceberg that pops up above the waves. We are convinced that it is there, but access to it is almost impossible. This is the mystery of Massalia. Massalia is the forgotten Colossus…”

An article from http://periklisdeligiannis.wordpress.com

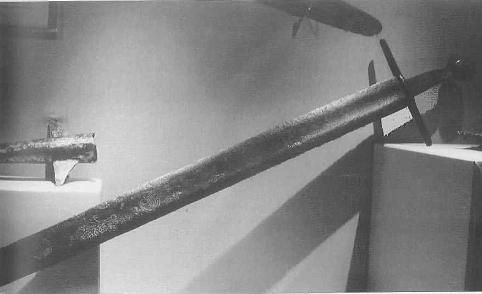

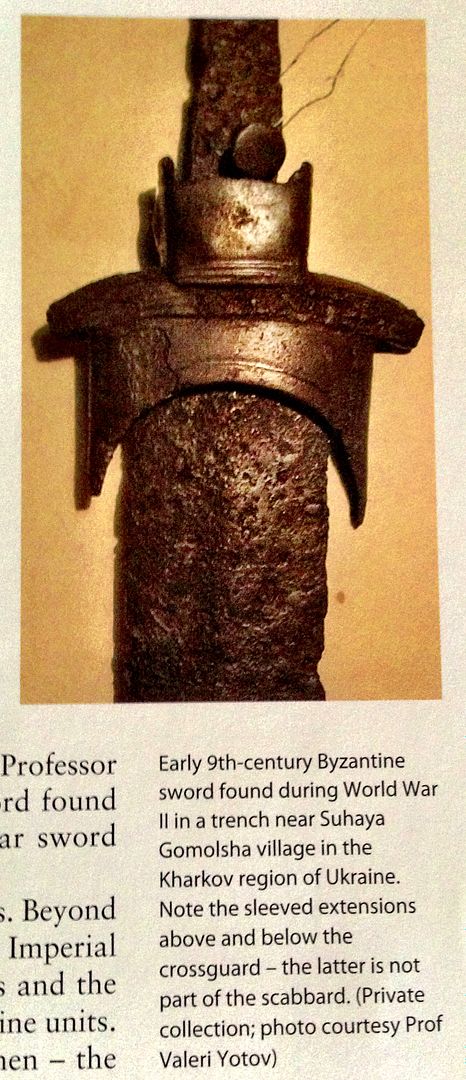

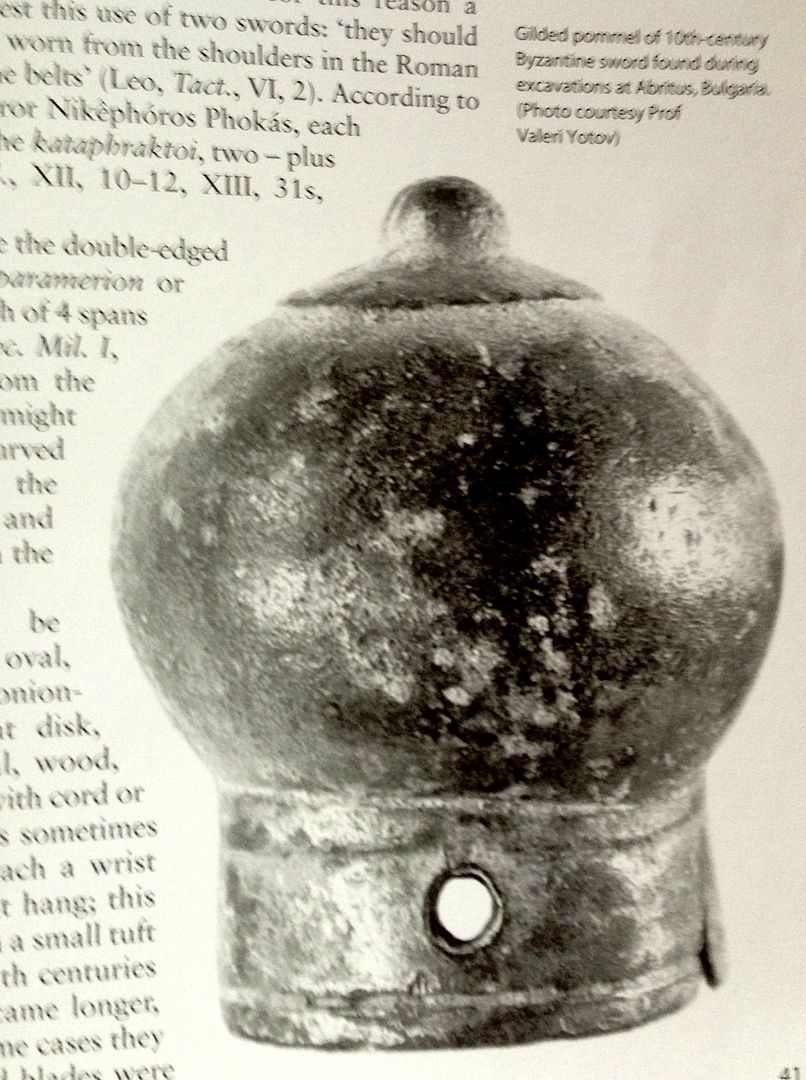

Here the Type R pommel is shown affixed to the end of a hand and half or two handed sword of the later Medieval period:

Here the Type R pommel is shown affixed to the end of a hand and half or two handed sword of the later Medieval period: