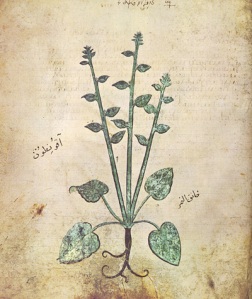

Monkshood – Aconitum napellus, Wolfsbane - Aconitum lycoctonum; and other species

Aconite is a powerful plant, used in the past as a medicinal herb, a poison and in potions for incantations. It belongs to the Aconitum genus of flowering plant belonging to the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae).

There are over 250 species of Aconitum. The most common plant in this genus, Aconitum napellus (the common Monkshood) was considered to be of therapeutic and of toxicological importance. These herbaceous perennial plants are chiefly natives of the mountainous parts of the northern hemisphere, growing in moisture retentive but well draining soils on mountain meadows.

There are over 250 species of Aconitum. The most common plant in this genus, Aconitum napellus (the common Monkshood) was considered to be of therapeutic and of toxicological importance. These herbaceous perennial plants are chiefly natives of the mountainous parts of the northern hemisphere, growing in moisture retentive but well draining soils on mountain meadows.

Some species of Aconite were well known to the ancients as deadly poisons. It was said to be the invention of Hecate from the foam of Cerberus, and it was a species of Aconite that entered into the poison which the old men of the island of Ceos were condemned to drink when they became infirm and no longer of use to the State. Aconite is also supposed to have been the poison that formed the cup which Medea prepared for Theseus. The Greeks hailed it as the Queen of Poisons, and until the 20th century, it was the deadliest toxin known to man.

The leaves and root yield its active ingredient, a potent alkaloid called Aconitine, which was frequently used to poison the tips of hunting darts or javelins. Until its toxic properties were discovered, tincture or liniment of aconite was used to relieve sciatica, neuralgia and rheumatism, for the heat-production and mild anaesthetic properties of the potion gave comfort to many an aching joint. However, its popularity took a plunge when it was discovered that the mere rubbing of preparations on skin produced symptoms like poisoning by ingestion, and thereafter was sought primarily by those who had more sinister uses for the plant. Already the author Nicander of Colophon (fl 130 BC) advised of aconite toxicity.

The poison works by targeting the cardiovascular and central nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract. All the species contain the active poison Aconitine, which exists in all parts of the plant, but especially in the root. The poison takes effect quickly. At one time, Aconite was a homeopathic remedy used in western medicine. Today, Aconite use in medicine has been discontinued in favour of safer medications.

The poison works by targeting the cardiovascular and central nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract. All the species contain the active poison Aconitine, which exists in all parts of the plant, but especially in the root. The poison takes effect quickly. At one time, Aconite was a homeopathic remedy used in western medicine. Today, Aconite use in medicine has been discontinued in favour of safer medications.Ancient knowledge of Aconite usage

The Greeks called Aconite lykotonon, meaning wolf slaying (Wolfsbane); this plant earned the name because it was rubbed on the arrows used when hunting wolves. Several species of Aconitum have been used as arrow poisons. Soldiers would dump aconite down wells in order to poison an enemy’s water supply.

Monkshood originated from the spittle of the beast Kerberos was dripped on the ground and this lead to the sprouting of Monkshood.

The art of poisoning was carefully cultivated in Rome, and became a flourishing industry since the early Emperors. Our knowledge of poisons available during Roman times is derived from the writings of Dioscorides, Scribonius Largus, Nicander, Pliny the Elder, and Galen. Poisons were of vegetable, animal and mineral origin. Vegetable poisons were best known and most frequently used. They included plants with belladonna alkaloids, e.g. henbane, datura, deadly nightshade and mandrake; aconite from monk’s hood; hemlock, hellebore, colchicum (from autumn crocus), yew extract and opium.

Galen understood the very deleterious qualities of botanical poisons, some cultivated for nefarious use, and others combined with beneficial drugs to engender stimulant effects (aconite, hyoscyamus, mushrooms, hemlock, mandrake, this last common in Roman times as a reliable anaesthetic). Galen commanded the technical details, best recorded in Greek by Dioscorides of Anazarbus, of animal, botanical, and mineral pharmacology.

In De Materia Medica (“The Materials of Medicine”), Dioscorides describes two different plants, the first Akoniton lycoctonum, which was used to kill panthers, wolves, and other wild beasts, and as an anodyne (pain reliever) in eye medications. In the next chapter, he describes “the other aconitum,” Aconitum napellus (monkshood), which also is toxic. Aconitum napellus is so named, says Theophrastus, because the tuberous root of the plant was thought to resemble a small turnip (napus) and “in this root resides its deadly property” (the alkaloid Aconitine). He goes on to say that, depending upon how it is compounded, the effect of the poison can be immediate or fatal in several months or even a year or two, the longer the time, the more painful the death. In general, it was deadly to any four-footed animal and “kills them the same day if the root or leaf is put on the genitals”.

Byzantine usage of Aconite as a poison

Of the 88 emperors who reigned from 324 to 1453— from Constantine I to Constantine XI— 29 died violent deaths, including several poisonings. Evidence for the use of aconitum as a poison in the Byzantine period can be found in the case of Emperor John I Tzimisces (ruled 969—976), who appears to have been poisoned by a disgruntled eunuch. He died suddenly in 976 on his return from his second campaign against the Abbasids, and was buried in the Church of Christ Chalkites, which he had rebuilt. Several sources state that the imperial chamberlain Basil Lekapenos poisoned the emperor to prevent him from stripping Lekapenos of his ill-gotten lands and riches.

Nowadays, Aconite’s natural habitat comprises the lower mountain slopes of the north portion of the Eastern Hemisphere; from the Himalayas through Europe to Great Britain. The Via Egnatia, one of the most important roads in the Byzantine Empire, built during the Roman Empire, to facilitate the communication between Rome and Constantinople, and connecting Durrеs to Lychnidos (Ohrid), Thessalonica (Thessaloniki), Adrianople (Edirne) and Constantinople (Istanbul), is known to be the spiritual and cultural axis, first for the spreading of Orthodox Christianity in South East Europe, and later on the spread of monkshood.

References

• “Poisons, Poisoning, and Poisoners in Ancient Rome”, Francois P. Retief & Louise Cilliers

• “Drugs for an Emperor”, John Scarborough

• “Medicine in the Crusades: warfare, wounds, and the medieval surgeon”, Piers D. Mitchell

All figures were borrowed from public domains in the Internet.

Related articles:

Eighteenth Annual Runciman Lecture by Judith Herrin - “We are all children of Byzantium”